Patterns, anticipation and participatory futures

Abstract

Patterns embody repeating phenomena, and, as such, they are partly but not fully detachable from their context. ‘Design patterns’ and ‘pattern languages’ are established methods for working with patterns. They have been applied in architecture, software engineering, and other design fields, but have so far seen little application in the field of future studies. We reimagine futures discourse and anticipatory practices using pattern methods. We focus specifically on processes for coordinating distributed projects, integrating multiple voices, and on play that builds capability to face what’s yet to come. One of the advantages of the method as a whole is that it deals with local knowledge and does not subsume everything within one overall ‘global’ strategy, while nevertheless offering a way to communicate between contexts and disciplines.

Anticipation — Design patterns — Pattern languages — Futures Studies — Scenario planning — Applied games

1 Introduction

In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is natural to ask: could we have been able to collectively anticipate the spread of zoonotic diseases, understand possible reactions, and formulate more adaptive responses? Many individuals anticipated that something like this was coming (Yong, 2018; Karesh et al., 2012; Schwartz, 1996; Sardar, 2010; Sardar and Sweeney, 2016). Our collective struggles have shown that we need to improve our anticipatory capabilities, that is, the capacity to act in response to or in preparation for a potential future reality Zamenopoulos and Alexiou (2020). As the virus spread from one corner of the world to another, it was no longer simply a question of putting a stop to the disease, and not simply a biomedical issue. Pandemics belong to a class of complex problems with social, political, and economical layers. While we are not going to solve the pandemic in this paper, the complex challenge motivates the issue we want to explore: how can communities learn to better anticipate together.

Of course, people have been finding new ways to think about the future together for a long time. For example, Ariyaratne (1977) tells the story of a rural group who were finally able to complete an important construction project. After 15 years of deadlock spent waiting for outside investment, they were called to a community meeting where they figured out that they could do the job with their own labour. As dialogue and inquiry gave participants new ways to articulate and develop their thinking together, the nature of the problem they faced became easier to understand and resolve.

The methodology we will develop here centres on design patterns: succinctly, solutions to problems arising in the context of a repeatable activity. We propose to use design patterns to structure anticipatory peer learning as a way to relate to possible future scenarios. The link between design and the future has been aptly summarised: “Design is future creating and not future guessing” (Banathy, 1991, p. 47). However, the relationship between the well-established design pattern methodology and futures studies has seen relatively little previous development.

After defining and giving examples of how design patterns have been used in other fields, we then examine how they can help create peer learning experiences to explore and prepare for the future. We outline a process of Open Future Design that we elaborate with three patterns that can be applied to collaboratively anticipate the unknown:

-

•

Create a roadmap as a tool to guide collaborative creative work.

-

•

Use scenario planning as a quasi-democratic approach to organise thinking about the future.

-

•

Play games in a collaborative manner to explore possible futures.

Our results present a synthetic, literature-based, treatment of these topics by way of design patterns. Whether the future holds a catastrophe, or something much better, patterns can help us evolve in our collective awareness today.

1.1 Background

Life itself is intrinsically anticipatory (Poli, 2012, 2020) and prefigurative schemas are relevant to the way we learn (Spiro et al., 1996). However, as a society, we are not guaranteed to be able to produce a viable outcome out of disparate individuals’ capacities to think about the future. How the challenges we face are understood depends very much on who is brought to the table, and how their discussions are organised. We have chosen to focus on pattern methods here because they seem to offer the prospect of being useful for developing viable, thriving, collective outcomes.

As Covid-19 rages out of control in some places, it is easy to forget that humans have largely eradicated or successfully controlled other diseases (e.g., polio, ebola, leprosy). While design patterns do not directly prevent the spread of disease, they can help prevent uncareful thinking — the consequences of which have included failing to anticipate a problem (as happened in many places with Covid-19 in December 2019 to February 2020) — or becoming too complacent based on previous successes (many people regularly choose not to get a flu shot). Patterns have been used to support and structure discourse around complex technical systems, and we feel they have much to offer in a futures studies context.

Reflecting on the history of design-pattern discourse, Shalloway and Trott (2005) remark that the related notion of a ‘cultural pattern’ has received attention in anthropology (Benedict, 1934, 1946). Likewise, Joseph Campbell proposed the monomyth of the hero as an ‘archetypal pattern’ that is embedded in myths and stories across diverse cultures and historical periods (Campbell, 1949) and Inayatullah noted that historians have understood historical trends in terms of patterns (Inayatullah, 1998a). ‘Design patterns’ in a general sense have long supported both small-scale and mass-manufacture of material objects and structures, ranging from clothing and ceramic ware to city-scale planning and, arguably, beyond.

Notwithstanding these precedents, the concept of patterns with which we are concerned here originated with the architect Christopher Alexander and his collaborators in the 1960s and 1970s (Alexander et al., 1977). One feature of their proposed pattern-based approach was to enable all stakeholders to participate in the process of architectural design. Additionally, they promoted a natural quality found in traditional architecture, versus the artificial one due to central planning (Alexander, 1965).

Alexander’s notion of an architectural pattern language was later adopted and adapted within the field of computer programming (Beck and Cunningham, 1987; Gamma et al., 1994). This trend received a large boost with the invention of wiki software, which was first used to collect and curate collections of such patterns (Cunningham and Mehaffy, 2013). Subsequently, ‘design pattern’ methods roughly in the Alexander style have been applied to other domains, including social activism (Schuler, 2009), the transition movement (Hopkins, 2010; TransitionNetwork.org, 2010), organizational development Manns and Rising (2015), disaster prevention Furukawazono et al. (2013), and mental health Pierri and Warwick (2016). Particularly relevant to our interests, Schuler (2009) speaks about patterns as conceptual tools for the future, and developed a pattern called “Future Design.” Iba develops a future-oriented view on pattern language discourse, with a recent presentation on “Creating Pattern Languages for Creating a Future where We Can Live Well” (Iba, 2019).

Since the definition of a pattern has been criticized for being inexplicit and inadequately explained (Dawes and Ostwald, 2017) and treatments by different sources vary, we would like to begin by explaining our understanding of the term design pattern. We recognise that some readers may bring their own existing understandings of this term, and that some will have no previous familiarity with it at all.

As our starting point, we take Alexander’s phrase: “Each pattern is a three-part rule, which expresses a relation between a certain context, a problem, and a solution” (Alexander, 1979, p. 247). However, Gabriel (2002) emphasises that Alexander’s full description of patterns goes well beyond the one sentence quoted above. Leitner supplied the following further summary text: “Patterns are shared as complete methodic descriptions intended for practical use by experts and non-experts” (Leitner, 2015) [emphasis added].

As we look into the matter two central elements emerge. Like an ellipse, the concept of the design pattern has two foci: context and community. The context is the type of activity which is being considered, such as designing a building or writing software. Communities include stakeholders — experts and non-experts alike — who are involved with or affected by a particular project. Also central to Alexander’s pattern-based methodology is the notion of a pattern language, in which each pattern description itself is contextualised by related pattern descriptions that deal with related problems. By working together as a whole, a pattern language produces coherent entities (Alexander, 1999). Within a specific design challenge, cascading patterns overlap to build out a design solution: for example, to fully develop a building, one would require a pattern for a suitable type of roof.

A pattern identifies how a community may proceed to obtain an outcome by making certain choices and applying specific methods to suitable materials. At the heart of the design pattern method is the feature of practicality. Each pattern description, when followed, should help the people using it — the community — overcome some real or potential conflict (Alexander and Poyner, 1970, pp. 9-10).

We will argue that patterns can be used to promote the organic, vital quality of resilience, that is, “not to be well-adapted, but to adapt well” (Downing (2007); quoted in Tschakert and Dietrich (2010)). We find the ‘non-expert’ portion of Leitner’s definition particularly important and hope to explain our ideas in an accessible way.

The most tangible metaphor is to treat each pattern as a journey, “a path as a solution to reach a goal” (Kohls, 2010, 2011). In this treatment, patterns are understood to have an initial condition and an end condition, defined within some context, and the corresponding problem is understood to be that of finding a good way to move from the initial state to the goal.

The economist Elinor Ostrom related Alexander’s pattern language to Arthur Koestler’s notion of ‘holons’ — stable components “in an organismic or social hierarchy, which displays rule-governed behavior” (Ostrom (2009, p. 11); Koestler (1973)). This citation makes explicit the analogy between patterns and Ostrom-style institutions. Ostrom’s framework understands an institution as a stable set of action-situations and proposes that each such situation be understood as a whole, while simultaneously being part of a larger social arrangement and a result of particular circumstances. In short, pattern language and institutional design are seen to be closely compatible.

In their applications within the computing discipline, patterns are typically written down with a template for easy communication and discussion. For example, alongside “Context”, “Problem”, and “Solution”, a typical template may include things like “Rationale” (reasons for preferring this specific solution over other possible solutions; Meszaros & Doble, 1997) and “Examples”. Typically a picture is included to serve as a mnemonic. Corneli et al. (2015) added a “Next Step” facet to the template they used, with the implication that each pattern is imperfectly realised and that further steps should be taken to manifest it within a collaboration.

Patterns have also been discussed in explicitly computational terms, though that direction of work remains mostly at the level of a proposal (Alexander, 1999; Moran, 1971), which has seen limited discipline-specific uptake within architectural design (Jacobus, 2009; Oxman, 1994). As a whole, the pattern discipline continues to evolve as an active area of research, particularly in computing disciplines. Several parallel yearly conferences are devoted to the exploration of themes touched on here, with some of the most developed contributions appearing in the Transactions on Pattern Languages of Programming book series. The specific contribution we make in this paper is to unite the pattern language and futures discourses as a coherent whole.

1.2 Pattern(s) as anticipatory method

In an everyday sense, ‘patterns’ are elements of an environment that recur in time or space. Because we expect them to recur, the patterns we recognise bear on our thinking about the future. The methodology we apply below is the reanalysis of existing future-oriented discourse within the specific constraints of the design pattern approach. The goal is to reimagine and reassemble it “together as a different version to bring out something latent or implicit in the original” (Handelman, 1998, p. 85).

As we reviewed above, we refer here to a specific methodological system centred on pattern descriptions that are intended for practical use (Leitner, 2015). Patterns of this form are accompanied by and embody principles that can lead from problem identification to problem solution within a given domain.

In concrete terms, we imagine how existing future-oriented discourses can be discussed and thought about using the pattern format. If the goal of future planning is to move from being reactive to being proactive, patterns methods have much to offer: they can help imagine and anticipate possible futures, and can help communities build resilience.

Through the comparative analysis of different future-oriented discourses vis-à-vis design patterns, we reimagine patterns as being something more than design tools: they become the building blocks for possible futures. Used in this way they present a way to “deconstruct […] conventional thinking to produce a shared view of possible future outcomes that can break existing paradigms of thinking and operating” (European Foresight platform, 2020).

From the many existing approaches to scaffolding anticipation—including speculative fiction (Gill, 2013; Liveley, 2017; Wagner-Lawlor, 2017), design fiction (Danoff et al., 2019; Kerspern, 2019; Raymond et al., 2019) prospective studies (de Jouvenel, 2004) and predictive statistical models (Arslan and Shamma, 2006)—we get limited insights about how to engage together. It is understood that anticipatory behavior can be provoked and improved (Bishop, 2018); and as individuals, we can engage in anticipatory learning, “the general mechanism of learning to generate predictions or learning a predictive or forward model of an encountered environment or problem” (Butz and Pezzulo, 2012). We see design patterns as filling a gap that addresses participatory anticipatory learning for complex problems requiring a group response.

2 Open Future Design: Patterns for anticipating the future

In this section we use design patterns to analyze three approaches to thinking about the future, namely: roadmaps, scenario planning, and play. We posit that the process of anticipation requires a set of choices that will be associated not only with our vision of the future — values, situations, materialities — but also with the process in which this anticipation happens.

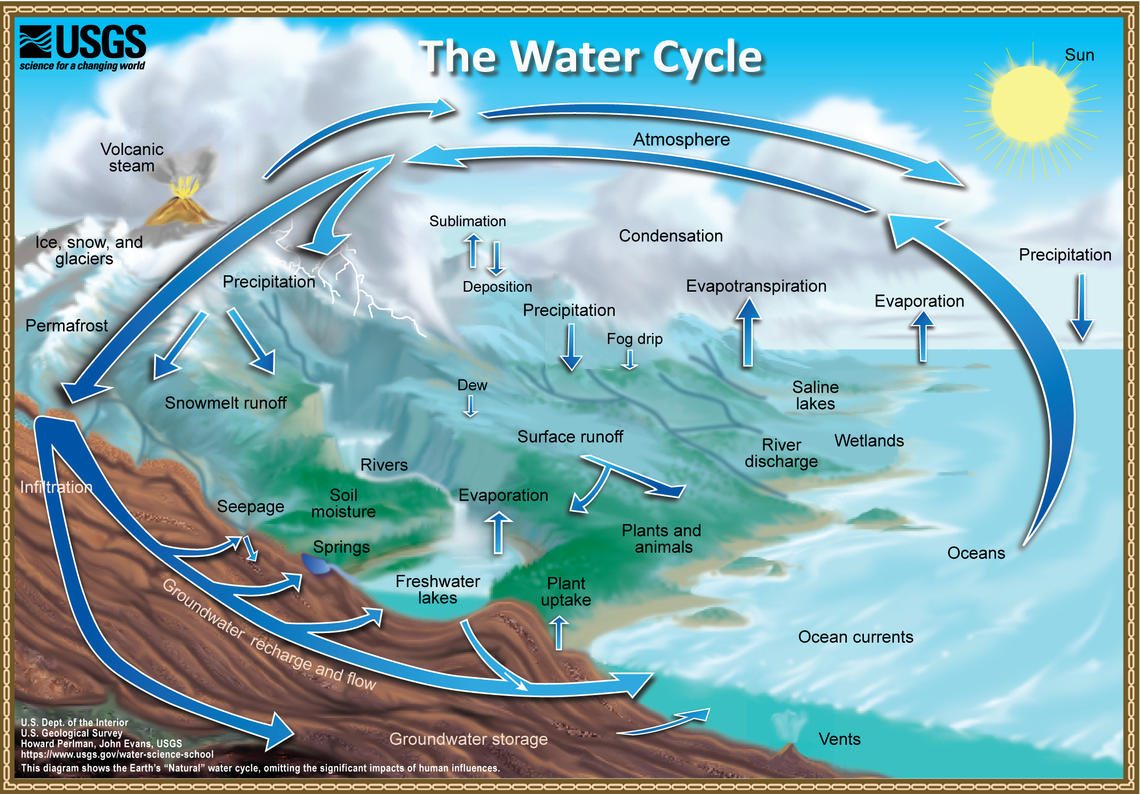

To begin our exploration of how design patterns relate to futures studies, we refer to Schwartz (1996, Appendix, pp. 241-248), viz., his “Steps to Developing Scenarios”. This process follows an outline with a striking similarity to a design pattern template. Both Alexander and Schwartz advocate the identification of driving forces in a context. However, unlike Alexander, Schwartz does not intend to resolve conflicts between the forces within a harmonising design. On the contrary, the aim in scenario development method is to understand how these forces might evolve and lead to diverse scenarios. As scenarios develop, they can serve as the ground for developing new design work in Alexander’s sense. With these aims in mind, the pattern Open Future Design serves as an entrypoint (Figure 1). As a mnemonic image, we chose to illustrate this pattern with a depiction of the water cycle, to show how Open Future Design, and subsidiary patterns that we describe below, represent an anticipatory cycle: as unknown and unexpected features materialise, our expectations develop and change.

PATTERN: Open Future Design

Context People need to coordinate, plan, and maintain social cohesion.

PATTERN: Open Future Design

Context People need to coordinate, plan, and maintain social cohesion.

If a culture can develop based on shared learning BUT there is no reliable oracle that can tell us what to expect;

Then use design pattern methods to articulate multiple futures. This work can be guided by further patterns, e.g., to develop - a language for projects → Roadmap - a language of future scenarios → Participatory Scenario Planning - a language of roles → Play to Anticipate the Future

2.1 The future via a roadmap

The success of collaborative learning and work is related to the conditions, processes, and tools that make such collaborations possible. One indicative example of ‘success’ is found in the Wikimedia Foundation (WMF). The WMF has made use of various planning exercises, ranging from the collaboratively produced “Wikimedia Strategic Plan” (Walsh, 2011) to the more centrally produced “Knowledge Gaps” (Zia et al., 2019) whitepaper. These activities should be understood in the context of an ongoing decline in participation in Wikipedia projects (Simonite, 2013), and the capture of online attention in various privatized media (Fuster Morell, 2011).

WMF’s strategy and plans are not dissociated from other practices in their projects. Structured guidance is made available to contributors to Wikimedia projects at all stages. Such guidance ranges from policies to tutorials, and helps contributors produce and maintain content to the benefits of the entire user community. Specific guidance on how to participate in data analysis and other planning activities that can help steer the project is available.

The culture around maintaining, updating and using such anticipatory artifacts comprises a system for governance. For example, online governance may evolve along the bottom-up lines proposed by Schneider et al. (2020). In the WMF example, the context, problems, and solutions are relatively explicit — e.g., gaps in knowledge should be filled to make Wikipedia more inclusive — and the community is included in both framing the problem and shaping the solution. On the other hand, justifiable doubts are likely to arise among constituencies who are brought into a “culture of consultation” (Featherstone, 2017) that is concerned, not with authentic community power, but with establishing and rubber-stamping the semblance of participation.

One way to enhance community power is to make plans based on pattern methods. In what might be a best case scenario, the “Roadmap” pattern from Corneli et al. (2015) becomes the entry point to a “living language” made up of other evolving patterns Alexander et al. (1977), each pointing to clearly designated next steps. While any notion of a plan presumes an anticipation of outcomes, the Roadmap may not be linear and directed towards one goal. It may instead be an organic tool for coordination across variables such as time, groups of people, and software. In the Scrum agile project management methodology, the “Product Roadmap” is complemented by a “Product Backlog” that offers a best-guess linear path through the various branching paths contained in the roadmap, while the roadmap itself keeps track of all anticipated alternatives as well as dependencies between tasks (Sutherland and others, 2019, p. 220, pp. 222-223).

We can consider the pheromone trails of ants as an example of an adaptive Roadmap in nature. By analogy, human participants in a collaborative design process should, metaphorically, have their antennae out to detect and respond to developing situations, and should develop suitably immediate methods for sharing meaning with each other. Notice that by anticipating future conflicts, we can take steps in advance to prevent and mitigate the problems that might ensue. This connects the Roadmap pattern with the broader themes of improving our ability to anticipate the future and resiliency. Figure 2 re-summarizes the Roadmap pattern, and highlights its nested context, in which the immediate community of users must adapt to a broader context in motion.

PATTERN: Roadmap

Context a group needs to coordinate its activities over a period of time.

PATTERN: Roadmap

Context a group needs to coordinate its activities over a period of time.

If the landscape is complex and not completely knowable BUT adjustment to action based on feedback is possible;

Then use an explicit mechanism to share information about goals, obstacles, methods, and resources.

Example Everyday roadmap languages include both iconic map and road sign symbols; when people are confused or lost they may ask for help or try to find their own way back to the road using other informal languages.

2.2 The future via peer learning and scenario planning

While scenario planning can be carried out by groups of experts, there is the danger that the life experiences and opinions of other people who are affected by their planning will not be considered. This could lead to a narrow understanding of the problem and a limited vision of what the future can look like. In participatory scenario planning, the activities are carried out by a community of non-experts with the experts or designers limiting their role to facilitation and moderation (Johnson et al., 2012). For instance:

-

•

The Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research project in Mali held a workshop at which 38 people including farmers, journalists, local leaders, forest officers, extension workers, policy makers, and representatives of NGOs and District Councils collaborated to produce scenarios for the future of agriculture (Johnson et al., 2012; Totin et al., 2018).

-

•

Agricultural development workshops in Nigeria included a teacher/researcher, a journalist, an engineer, an animal nutritionist, a camera operator and head of a women’s group (Olabisi et al., 2016).

-

•

In the Minnesota 2050 project, participants were selected from a variety of professions and leadership roles to produce scenarios for energy and land use, and combined modelling with scenario planning (Olabisi et al., 2010).

In all of these examples, scenario planning was taken out of the hands of the experts, but scientists and other consultants still played a specialized role. A varied community that designs and produces something by and for themselves would be more fully analogous to Alexander’s vision of community-designed architecture (Alexander et al., 1977). If community members could be involved as scenario planners, or as architects, why not also involve them as citizen scientists or modellers? Wildschut (2017) points out that the ‘local knowledge’ of citizens can make the inquiry process more robust: “Citizens have valuable knowledge that is often out of reach for university scientists.” Another related people-centered approach is described by the DesignJustice.Org (2018) whose principles are addressed to “people who are normally marginalized by design.” Whether in a scenario planning, scientific inquiry, or design process, participants need more than just ‘access’, i.e., not just access to existing scholarly materials produced elsewhere, but also to a platform and literacies/capabilities that allow them to contribute and negotiate; Heidegger used the term Zuhandenheit: “readiness-to-hand, handiness.” Existing collections of design patterns can help address these requirements. For example, many of the “Wise Democracy” patterns elaborated by the Co-Intelligence Institute (2019) would carry over well to participatory scenario planning. Specific patterns include: (#30) “Expertise on tap (not on top)”, (#33) “Feeling heard”, (#82) “Systems thinking”, and (#94) “Wise use of uncertainty”.

The pattern language contains other useful hints for scenario planners. We can elaborate with a concrete example. Johnson et al. (2012) made this observation based on their experience with participatory scenario planning: “Groups with too little diversity converge quickly and without exchanging contrary ideas, and will necessarily develop fewer options for action. Yet too much diversity can hobble a group and overwhelm a process with too many conflicting values and perspectives.” We do not consider that there is such a thing as “too much diversity” in any absolute sense, only limitations to a group’s ability to integrate diverging visions of the future and to learn from conflict. Indeed, since managing conflict seems to be a key concern here, it would make sense to express this experience with a design pattern. One benefit of diversity was noticed by Schwartz (1996, p. 97): “being part of several networks not only opens up diverse arenas, but allows you to cross-check the insights that emerge among people from vastly different places.” Relevant patterns are again found in the Wise Democracy pattern language: (#26) “Diversity” and (#88) “Using Diversity and Disturbance Creatively”. Scenario planners who are concerned that there is too little or too much diversity within their dialogue could refer to these patterns to enrich their thinking on the matter with to-hand knowledge. An example of where this could have been helpful: Ewing (2018) describes how, when forty-nine individual public schools in Chicago closed, students were not equal participants in the decision and were left to deal with the “intense emotional aftermath” (p. 159). She suggested that “perhaps CPS can learn from the school closures to create structures that let stakeholders participate meaningfully in decisions so as to incorporate community voices” (p. 161).

Patterns could help with further specifics of process. One reference point in futures studies is the Delphi method RAND Corporation (2020). However, in Delphi, summaries are produced by a facilitator synthesising expert feedback and sharing it back out to participants. Delphi’s “goal is to reduce the range of responses and arrive at something closer to expert consensus” (ibid.). In a world in which we respect each participant as an expert with relevant experiences, we need more complex ways to integrate multiple voices. The pattern methodology itself has the potential to incorporate contributions from diverse stakeholders, by foregrounding context and community at each stage. It is worth pointing to extant patterns for pattern writing (Iba and Isaku, 2016; Meszaros and Doble, 1997) and workshopping (Coplien and Woolf, 1997; Gabriel, 2002); and to criteria for evaluating patterns throughout their lifecycle (Petter et al., 2010). We summarise these reflections in a “Participatory Scenario Planning” design pattern in Figure 3.

2.3 The future via play

Before the future arrives, one way to prepare is by playing: this not only simulates different scenarios, but also helps us experience what it is like to live in them. “Play can help kids learn, plan and even persevere in the face of adversity” (Willyard, 2020). There can be other benefits—for adults as well. According to legend, the ancient Maeonians developed various games (played with dice and balls, as well as a lottery) that helped them endure hunger (Herodotus, 1975, p. 43). According to Huizinga (1949), play is in fact fundamental for civilization. In a metaphysical view that centers aleatory practice, “the game and fate fuse into destiny” (Gane, 1991, p. 25).

PATTERN: Participatory Scenario Planning

Context you want to plan for possible future scenarios.

PATTERN: Participatory Scenario Planning

Context you want to plan for possible future scenarios.

If you have an interested group BUT no “expert” has all the answers;

Then pool the collected expertise of the affected communities.

Example the Next Generation Services project (http://nextgenpsf.co.uk) used participatory scenario planning to imagine different plausible AI futures, which were then used in design sprints to expose professional services firms to potential AI challenges and opportunities.

Games offer ‘oblique strategies’ (à la Eno & Schmidt — see Taylor (1997)) for anticipating the future. They transform the future into something we can play with and thereby expand the horizons of what we believe is possible in the coming days and years (Sweeney et al., 2019). This has not gone unnoticed by futurists. For example: in 2015, United Kingdom government officials developed a futures gaming process called the “Scenario and Implication Development” system to play at the 5th edition of the Global Strategic Trends review (Sweeney, 2017). Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) (Inayatullah, 1998b) is a well known tool for imagining possible futures: at the conference “Futures Studies Tackling Wicked Problems” in Finland, attendees played a CLA game to test out different scenarios, and the game allowed them to include a diversity of perspectives (Heinonen et al., 2017).

Examples of recent games designed to explore possible futures include:

-

•

The Oracle for Transfeminist Technologies (Varon et al., 2019): a card deck designed to collectively envision and share ideas for transfeminist tech in the future. This game is based on the assumption that people who are excluded by technology in today’s world are qualified to design future scenarios (Varon, 2020).

-

•

Flaws of the Smart City (Friction, 2016): a card game exploring smart-city futures (that architects like Alexander might also enjoy playing). The co-founder of Design Friction explains how the game tries to make it easier for those outside the design community to easily use future scenarios and design fiction (Kerspern, 2019).

-

•

HEY! Imaginable Guidelines (ŞanalArc, 2018): another city themed game in which participants use cards to discover how cities are designed by selecting topics that are necessary, desirable, or irrelevant to the urban-design problem they are trying to solve (Hattam, 2019). The game provokes players to make changes and continue the conversation after play has concluded.

-

•

Equitable Futures: a future-oriented game produced by the Institute For the Future. It is used to develop understandings of challenges to overcome as players try to find new ways to build a more equitable future and re-imagine our worlds for 2030 (Finlev and others, 2019).

Although it was not designed by futurists, the cooperative board game Pandemic (Leacock, 2008), where players work together to find a cure for a virus spreading across the world, has served a similar purpose. It has helped people cope with the current Covid-19 pandemic (Genovese, 2020; Leacock, 2020), including doctors and medical students (Woo, 2020; Borrelli, 2020). Employees of the Centers for Disease Control previously commented that the game “reflected the reality and values of public health” (Lee, 2013). In this case the upshot is that players have been experimenting with how to solve a pandemic, thanks to this game, since 2008.

There are existing design patterns for creating games and using them to learn. Iba’s pattern “Playful Learning” is based on the observation “It is easier to enjoy learning something new if you take pleasure in the results” (Iba, 2018, p. 9); for instance, one might opt to learn to program by programming a video game, or practice a foreign language by playing Two Truths and a Lie. The genre of “‘Applied Games’ or ‘Games with Purpose’ … seek to harness our natural curiosity and playfulness in the search for new knowledge” (Rawlings, 2016). One sub-genre is described in Schuler’s “Socially Responsible Video Games Pattern” where games are used as a vehicle to introduce real-world issues in an interactive format (Schuler, 2008).

As Iba’s “Playful Learning” pattern stated, the games themselves need to be fun and tangible. As one simple step in this direction, Iba created physical cards for his patterns, so that playing with them would be more enjoyable. Collections of game design patterns are also available that can help designers build in features that make games attractive and interesting (Kreimeier, 2002).

Figure 4 summarises the foregoing reflections as a pattern, Play to Anticipate the Future. Perhaps future definitions for play will catch up with the reality this description embodies: none of the five current definitions for this word as a verb in the Webster dictionary include anything about learning or the future (Merriam-Webster, 2020).

3 Discussion

Our presentation at the Anticipation 2019 conference took the form of a scripted dialogue that we invited audience members to read aloud. We hoped that this might spark conversation, by modelling the kind of participatory dialogue we wanted participants to feel comfortable having—better than one presenter speaking to the audience the entire time. As it happened, the first comment we received from one of the volunteer readers pushed back vigorously against the format: “Why did you ask us to read a script, rather than improvise?” Subsequently, this led us to explore more authentically collaborative methods for anticipating the future. Central to this process was the fact that we are a diverse international group of peers who were prepared to think together about our local concerns, investments, and activities. This paper has shown how the pattern method can be used to develop a mindset for collaborative anticipation that embraces diverse points of view. Such usage was already hinted at by Moran (1971), who wrote that “From the point of view of methodology, it is not so important how good each pattern is, but only that each one is transparent and open to criticism and can be improved over time.”

With further application of the method, futures discourses could become more ‘generative’, i.e., refashioned as “a kit of parts … together with rules for combining them” (Alexander, 1968). To meet this need, the set of patterns would have to be more fully elaborated. In the domain of the built environment, Alexander (1999) refers to inspiration coming from “generative schemes that exist in traditional cultures” with “as few as a half a dozen steps, or as many as 20 or 50.” It is not simply a matter of adding more patterns — but one of understanding the unfolding processes that they represent, when taken together.

PATTERN: Play to Anticipate the Future

Context you want to have fun with friends, colleagues or acquaintances.

PATTERN: Play to Anticipate the Future

Context you want to have fun with friends, colleagues or acquaintances.

If you want to explore possible futures BUT time travel does not exist and you don’t know what to expect;

Then play a game that lets you experience a plausible future scenario together.

Example a bipartisan group of politicians, former civilian and military officials, and academics gathered to play a scenario planning game to anticipate the possible aftermath of a contested election: at the very least the scenarios they came up with managed to surprise them (Bidgood, 2020).

Pattern language development can give us another way to think and talk about the “process of language development” that already goes on inside institutions (Schwartz, 1996, p. 205). Further challenges include understanding complex interactions between contexts and communities that previously had little relationship with each other. Another concern is how to balance futures discourse with other pressing concerns: if we wait too long, or structure the discourse poorly, we will end up being reactive. One specific direction for development of the ideas would be to work jointly with the Participatory Modeling (PM) community, addressing concerns like “What are the major interpretation and communication issues in PM? Are there best practices to address these issues?” (Jordan et al., 2018). To be most applicable in this setting, the methods would need further elaboration, e.g., to become more computationally salient to address the specific needs of modelers, and to incorporate the developing insights from Alexander and others on what makes this method work well.

The vision of “Open Future Design” (§2) is to be open to almost any possibility when we imagine it. As a touchstone, when they are first suggested, beneficial future visions “should appear to be ridiculous” (Dator, 2019). However, in real life, there are scenarios we prefer to close off. We can prepare for various eventualities by experiencing these possibilities in games (§2.2) or other simulated encounters, rather than in real life.

A pattern-theoretic approach to futures links ‘futures studies’ to processes of growth and development. Community assembly of ecosystems and the growth of embryos are relevant natural examples of processes that have ‘futures’. These natural processes are ordered, not only in time but also in space. Reflecting on these examples, we see more clearly how it is that individual futurists — without the contexts in which their ideas could become meaningful — are like little bits of organs that are detached from the bodies and materials needed to function. Similarly, while science fiction can provide a ‘thinking machine’ (Doherty and Giordano, 2020), it cannot on its own provide historically robust alternatives to the global crises that we face. Narrative and design fiction methods (Gill, 2013; Liveley, 2017; Wagner-Lawlor, 2017) have been applied in design, and from there, reapplied in futures studies. When these methods are used to prepare effectively, we would be inclined to think of them as part of a “Roadmap” in the sense we used this term above (§2.1).

A roadmap is a kind of genetic code for a successful project: and here one should keep in mind that a genotype is not a simple blueprint (Pigliucci, 2010). You cannot create a roadmap in a vacuum and hand it to someone and expect it to work. Collaboration and communication are needed to create a useful roadmap and that process itself can become the largest part of the value of the roadmap. Once the plan is in motion and things start not to happen as expected, the roadmap can be used as a reminder of what was planned to help groups respond based on prior collaborative knowledge and understanding. The understanding it took to create it is key. It creates “resilience”.

Diversity — secured via patterns like “Participatory Scenario Planning” (§2.2) — can boost our collective immunity in a broad sense of that word (Wambacq and van Tuinen, 2017). Diversity allows our understanding of the whole to be enriched. Without it, we risk attacking potentially vital imagined futures, as when in autoimmune disease, the immune system attacks healthy body cells (Houwen and Rachmany, 2018). If we fail to consider and account for the needs of all stakeholders affected by decisions, we are not acting in alignment with our basic need for survival as part of humanity and part of the ecosystem on earth.

As we consider the needs and interests of broad cohorts of stakeholders we can position this work as a response to Kostakis et al. (2015) who argued for a development model based on “thinking global and producing local.” At the centre of their vision is a global pool of designs, which are put into production in local Fab Lab facilities. By contrast, in our work we have centred circumstances of cultural diversity and human relationships. In our view, the pattern method flips the Kostakis et al. formula on its head: patterns are primarily tools for thinking locally about particular contexts, individual relationships, conflicts and circumstances. Only secondarily and potentially does this lead to a shared global resource. More likely, pattern methods would simply strengthen local forms of resilience and better identify healthy futures.

Incorporating diverse communities into an ongoing futures discourse is a tall order and some humility is required. In contrast to design, which ultimately converges, futures-oriented activities are about producing diverse open-ended possibilities: this is akin to Deleuze’s remark that “the system must not only be in perpetual heterogeneity, it must also be a heterogenesis” (Deleuze, 2010). This is why reading a script — for example — is not necessarily the best way to motivate discussion about the future. As Sardar (2010) pointed out, future predictions do not actually provide us with foreknowledge. However, anticipation can provide future-readiness; with this in mind, a script could be reworked as a game that participants could “Play to Anticipate the Future” (§2.3) together.

The project we have embarked on will help to address the societal need for improved facilities of anticipation. Through the generative nature of the pattern method, users can become prepared for many outcomes and possibilities. A great strength of this method is that it can be used differently in different places, with no need of assembling everything into one unified ‘design’. We highlight some specific implications of the patterns we developed in Figure 5.

The individual points indicated in Figure 5 are at least somewhat plausible, e.g., Ali S. Khan from the CDC “became interested in Vaughan’s game [Plague Inc.] as a tool to teach the public about outbreaks and disease transmission because of how it uses a non-traditional route to raise public awareness on epidemiology, disease transmission, and diseases/pandemic information” (Kahn, 2013). Potentially even more exciting is to think about what the pattern methods offer if they were adopted on a broad scale. Like Escobar (2018) proposes, they could open up the possibility to design multiple pluriverses, where we do not just make plans focused on one choice but include diversity integrally in our thinking. Reanalysis of futures methods in light of the transdisciplinary pattern methodology has given us new insights into the way futures studies work, and how they might be practiced collaboratively, across domains and cultures.

EXAMPLES:

Looking back: how might the patterns we

wrote have helped in 2020?

•

In January, world leaders met online to simulate many global infection-spreading scenarios by playing Pandemic (Leacock, 2008), and Plague Inc (Ndemic Creations, 2012) to see how to contain or spread the virus.

•

In February, people in nursing homes and prisons engaged in participatory scenario planning, which helped shift the collective outlook of society at large, leading to more informed discussions, and safer health behaviours.

•

In March, national teams developed roadmaps for curricula teaching citizen science approaches of epidemiology, and students subsequently helped lead national recovery projects.

EXAMPLES:

Looking back: how might the patterns we

wrote have helped in 2020?

•

In January, world leaders met online to simulate many global infection-spreading scenarios by playing Pandemic (Leacock, 2008), and Plague Inc (Ndemic Creations, 2012) to see how to contain or spread the virus.

•

In February, people in nursing homes and prisons engaged in participatory scenario planning, which helped shift the collective outlook of society at large, leading to more informed discussions, and safer health behaviours.

•

In March, national teams developed roadmaps for curricula teaching citizen science approaches of epidemiology, and students subsequently helped lead national recovery projects.

Looking forward: How might things look in the future building on this work? • Everyone learns “history” in school, but not “future”: this material and associated techniques could become part of a new curriculum for futures. • Policy could develop via town-hall format discussions: rather than being based on Q&A, politicians would lead citizen teams in developing different scenarios. • E-sports could expand to explore plausible scenarios in games like SuperBugs (Nesta, 2016) where players race against the clock to keep antibiotics effective.

4 Conclusions

Our main results outlined several ways in which design patterns can be used to model future-directed activities. It is possible to envision scenarios that bring all of these methods together. For example, consider a gaming situation in which teams are completing, or a similar setting in which there are people acting with competing interests, with different scenarios thrown into the mix (resource depletion, regulatory changes, inflation, natural disasters, actions by other players, etc.) to test their reactions. Roadmaps could be used both in the competition and in research designs to make sense of the subsequent output and draw transferable insights from the exercise.

As we have noted, a key feature of the methods we have described is to promote heterogeneity of thought and behavior. Part of the purpose of participatory methods would be to make sure we have the right experts. For example, a nurse may have noticed things on the ward that epidemiologists would never have experienced. A pandemic team with the right balance of expertise and diverse community participants — with suitable methods for collaborating and learning together — will get better results than professional analysts, scientists, and university researchers working in isolation.

Which brings us to you, dear reader. We assume you wanted to learn about the subjects in the title: or perhaps this paper was assigned to you in school and you are reading it for a grade? Either way, we are excited to invite you to use and adapt these methods. For us, this work is likely to serve as a springboard for our efforts. We hope that the paper will be practical for you, too. Or, perhaps you think we are deluding ourselves with ivory tower navel gazing? — After all, even if the broad outlines of this work are correct, a degree of skepticism is warranted given that Alexander already shared relevant clues 20 years ago. Or perhaps your criticisms run the other direction, and you found the patterns too simplistic. We, of course, remain open to these and other criticisms. Future work might integrate design patterns and macrohistorical patterns for anticipation, or combine patterns and CLA (Inayatullah, 1998a, b) to connect diverse and divergent themes across multiple layers of experience and observation. Alternative methods described by Sools (2020) focus on observing how consideration of future outcomes affects present choices. Depending on what year it is when you are reading this, perhaps these integrative suggestions have already come to pass. If you think the points we raised in this paper are meaningful and valuable, then a likely corollary is that there will still be a lot of hard work to realise the full vision.

Acknowledgements

We thank Claire van Rhyn for bringing the Anticipation conference to our attention. We acknowledge the comments and participation in online seminar discussions of: Roland Legrand, Lisa Snow MacDonald, Verena Roberts, Charles Blass, Stephan Kreutzer, Giuliana Marques, and Cris Gherhes.

References

- The atoms of environmental structure. In Emerging Methods in Environmental Design and Planning, G.T. Moore (Ed.), pp. 308–321. Cited by: §1.1.

- A city is not a tree. Architectural Forum 122 (1), pp. 58–62. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- The timeless way of building. Oxford University Press. Cited by: §1.1.

- The origins of pattern theory: the future of the theory, and the generation of a living world. IEEE Software 16 (5), pp. 71–82. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1, §1.1, §3.

- A pattern language: towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press. Cited by: §1.1, §2.1, §2.2.

- Systems generating systems. Architectural Design 38 (December 1968), pp. 605–610. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §3.

- Organization of rural communities for group effort and self-help. In Food Crisis Workshop, Los Banos, Laguna (Philippines), pp. 23–24. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.

- Anticipatory learning in general evolutionary games. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, pp. 6289–6294. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.2.

- Systems design of education: a journey to create the future. Educational Technology Pubns. Cited by: §1.

- Using pattern languages for object-oriented programs. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- Patterns of culture. Houghton Mifflin Co. Cited by: §1.1.

- The chrysanthemum and the sword. patterns of japanese culture. Houghton Mifflin Co. Cited by: §1.1.

- Anticipation: teaching the future. In Handbook of Anticipation, pp. 1–10. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2.

- Q&A with the chicago creator of pandemic, the board game that has become all too real. Chicago Tribune March 5. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Anticipatory learning. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, N.M. Seel (Ed.), pp. 1007 978–1–4419–1428–6. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2.

- The hero with a thousand faces. Pantheon Books (The Bollingen Series. Cited by: §1.1.

- Wise democracy project. PATTERNS LIST version 2.0.. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.2.

- A pattern language for writers’ workshops. C Plus Plus Report 9, pp. 51–60. Cited by: §2.2.

- Patterns of peeragogy. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs, pp. 1–23. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.1.

- Wiki as pattern language. In Preprints of the 20th Pattern Languages of Programs Conference, Vol. PLoP’13, pp. 32. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- A fictional peeragogical anticipatory learning exploration [conference presentation abstract]. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2.

- What futures studies is, and is not. In Jim Dator: A Noticer in Time, pp. 3–5. Cited by: §3.

- Christopher alexander’s a pattern language: analysing, mapping and classifying the critical response. City, Territory and Architecture 4 (1), pp. 1–14. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1.

- Invitation a la prospective–an invitation to foresight. Bilingual Collection Perspectives–Futuribles. Cited by: §1.2.

- Letter preface. In Variations: The Philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, J. Martin (Ed.), Cited by: §3.

- Design justice network principles. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 15, 4, pp. 1186 13010–020–00089–0. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.2.

- What we may learn – and need – from pandemic fiction. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 15 (1), pp. 4. External Links: ISSN 1747-5341, Document, Link Cited by: §3.

- Adapting to climate change: achieving increased resilience and livelihood improvements. panel discussion. In Forest Day, Cited by: §1.1.

- Designs for the pluriverse radical interdependence, autonomy,and the making of worlds. Duke University Press. Cited by: §3.

- Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2.

- Ghosts in the schoolyard. University of Chicago Press. Cited by: §2.2.

- Divining desire: focus groups and the culture of consultation. OR Books. Cited by: §2.1.

- Equitable futures toolkit. institute for the future. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 4th item.

- Flaws of the smart city [card game]. Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 2nd item.

- Designing a pattern language for surviving earthquakes. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- An introductory historical contextualization of online creation communities for the building of digital commons: the emergence of a free culture movement. In OKCon 2011. Open Knowledge Conference Proceedings of the 6th Open Knowledge Conference, S. Hellmann, P. Frischmuth, S. Auer, and D. Dietrich (Eds.), Berlin, Germany. Note: Retrieved from External Links: Link Cited by: §2.1.

- Writers’ workshops & the work of making things: patterns, poetry…. Pearson Education. Cited by: §1.1, §2.2.

- Design patterns: elements of reusable object-oriented software. Addison-Wesley. Cited by: §1.1.

- Baudrillard’s bestiary: baudrillard and culture. Routledge. Cited by: §2.3.

- Pandemic — the board game — foreshadows current crisis. NJ.Com April 3. Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- The uses of genre and the classification of speculative fiction. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 46 (2), pp. 71–85. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.2, §3.

- Models and mirrors: towards an anthropology of public events. Berghahn Books. Cited by: §1.2.

- A card game designed to help urban communities plan for the future. bloomberg citylab. Note: Accessed 25 November, External Links: Link Cited by: 3rd item.

- Testing transformative energy scenarios through causal layered analysis gaming. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 124, pp. 101–113. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Penguin Books, London. Note: (Selincourt, R. A. and Aubrey Burn, eds.) Cited by: §2.3.

- Rethinking transition as a pattern language: an introduction. Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- So, you’ve got a dao … management for the 21st century: handbook for distributed and connected leadership 1.0. DAO Leadership. Cited by: §3.

- Homo ludens: a study of the play-element of culture. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. Cited by: §2.3.

- A pattern language for creating pattern languages: 364 patterns for pattern mining, writing, and symbolizing. External Links: Document Cited by: §2.2.

- Learning patterns: a pattern language for creative learning. CreativeShift Lab. Cited by: §2.3.

- Creating pattern languages for creating a future where we can live well. Note: INTERSECTION19 (Designing Enterprises for Better Futures). External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- Macrohistory and futures studies. Futures 30 (5), pp. 381–394. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1, §4.

- Poststructuralism as method. Futures 30 (8), pp. 815–829. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §2.3, §4.

- The disappearing architect: 21st century practice and the rise of intelligent machines. In 97th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, The Value of Design, pp. 159–165. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- Using participatory scenarios to stimulate social learning for collaborative sustainable development. Ecology and Society 17 (2). External Links: Link Cited by: 1st item, §2.2, §2.2.

- Twelve questions for the participatory modeling community. Earth’s Future 6, pp. 1046– 1057. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §3.

- Plague inc., centers for disease control and prevention. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §3.

- Ecology of zoonoses: natural and unnatural histories. The Lancet 380 (9857), pp. 1936–1945. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.

- Game design fiction: bridging mediation through games and design fiction to facilitate anticipation-oriented thinking. In 3rd Conference on Anticipation, Oslo Norway. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2, 2nd item.

- The tree and the candle. In Unity Through Diversity, W. G. and N.D. Rizzo (Eds.), Cited by: §1.1.

- The structure of patterns. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs - PLOP, Vol. 10, pp. 1–10. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1.

- The structure of patterns: part ii - qualities. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs - PLoP, Vol. 11, pp. 1–18. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1.

- Design global, manufacture local: exploring the contours of an emerging productive model. Futures 73, pp. 126 – 135. External Links: ISSN 0016-3287, Document, Link Cited by: §3.

- The case for game design patterns. Gamasutra Features. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Pandemic [board game]. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3, 1st item.

- No single player can win this board game. it’s called pandemic. New York Times March 25. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- The next monopoly? what “pandemic” teaches us about public health. public health matters blog. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Pattern theory: introduction and perspectives on the tracks of christopher alexander. HLS Software. Cited by: §1.1, §1.2.

- Anticipation and narratology. In Handbook of Anticipation, pp. 1–20. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2, §3.

- Fearless change: patterns for introducing new ideas. Addison-Wesley Professional. Cited by: §1.1.

- Play. In Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- A pattern language for pattern writing. In Pattern Languages of Program Design 3, pp. 656. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.2.

- (Artificial, intelligent) architecture: computers in design. Architectural Record 149, pp. 129–134. Cited by: §1.1, §3.

- Plague, inc [video game. Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 1st item.

- Our new game: how long can you survive against the superbugs?. Note: Accessed 25 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 3rd item.

- Using scenario visioning and participatory system dynamics modeling to investigate the future: lessons from minnesota 2050. Sustainability 2 (8), pp. 2686–2706. External Links: Link Cited by: 3rd item.

- Do participatory scenario exercises promote systems thinking and build consensus?. Elementa, pp. 1–11. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: 2nd item.

- Understanding institutional diversity. Design Studies 15 (2), pp. 141–157. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1.

- Precedents in design: a computational model for the organization of precedent knowledge. Design Studies 15 (2), pp. 141–157. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- A design science based evaluation framework for patterns. SIGMIS Database 41 (3), pp. 9–26. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §2.2.

- Changing the mental health system by design. In People, Place and Policy Conference: Governing social and spatial inequalities under enduring austerity, 15th September 2016, Sheffield, UK, Cited by: §1.1.

- Genotype–phenotype mapping and the end of the ‘genes as blueprint’metaphor. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365 (1540), pp. 557–566. Cited by: §3.

- Many aspects of anticipation. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, N.M. Seel (Ed.), External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- Handbook of anticipation. Springer International Publishing. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.1.

- Delphi method. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.2.

- Playing at science: how video games and science can work together. longitude prize. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Design, relational ontologies and futurescaping. In 3rd Conference on Anticipation, Oslo Norway. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.2.

- HEY! imaginable guidelines [card game. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 3rd item.

- The three tomorrows of postnormal times. Futures 75, pp. 1–13. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.

- Welcome to postnormal times. Futures 42 (5), pp. 435–444. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1, §3.

- Modular politics: toward a governance layer for online communities. External Links: 2005.13701 Cited by: §2.1.

- Liberating voices: a pattern language for communication revolution. MIT Press. Cited by: §2.3.

- Pattern languages as critical enablers of civic intelligence. In PUARL Conference, Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- The art of the long view: paths to strategic insight for yourself and your company. Doubleday. Cited by: §1, §2.2, §2, §3.

- Design patterns explained: a new perspective on object-oriented design. Addison-Wesley Professional. Cited by: §1.1.

- The decline of wikipedia. MIT Technology Review October 22. Cited by: §2.1.

- Back from the future: a narrative approach to study the imagination of personal futures. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23 (4), pp. 451–465. External Links: Document, Link, https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1719617 Cited by: §4.

- Two epistemic world-views: prefigurative schemas and learning in complex domains. Applied Cognitive Psychology 10 (7), pp. 51–61. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- A scrum book: the spirit of the game. The Pragmatic Programmers. Cited by: §2.1.

- Game on: foresight at play with the united nations. Journal of Futures Studies 22 (2), pp. 27–40. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Anticipatory games & simulations. In Handbook of Anticipation: Theoretical and Applied Aspects of the Use of Future in Decision Making, R. Poli (Ed.), pp. 1–29. External Links: ISBN 978-3-319-31737-3, Document, Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Introduction. the oblique strategies. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- Can scenario planning catalyse transformational change? evaluating a climate change policy case study in mali. Futures 96, pp. 44–56. External Links: Link Cited by: 1st item.

- Seeing transition as a pattern language conference booklet. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.1.

- Anticipatory learning for climate change adaptation and resilience. Ecology and Society 15 (2), pp. 11. External Links: Document Cited by: §1.1.

- The oracle for transfeminist technologies. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 1st item.

- The future is transfeminist: from imagination to action. Deep Dives. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: 1st item.

- Anticipating utopia: utopian narrative and an ontology of representation. In Handbook of Anticipation, pp. 1–21. External Links: Link, Document Cited by: §1.2, §3.

- Wikimedia movement strategic plan: a collaborative vision for the movement through. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.1.

- Interiority in sloterdijk and deleuze. Palgrave Communications 3 (1). External Links: Document, Link Cited by: §3.

- The need for citizen science in the transition to a sustainable peer-to-peer-society. Futures 91, pp. 46–52. Cited by: §2.2.

- How play energizes your kid’s brain. New York TImes. Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- How do doctors treating coronavirus relax? by playing the game “pandemic”. Wall Street Journal June 28. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.3.

- The next plague is coming. In Is America Ready? The Atlantic, Note: Accessed 24 November, 2020 External Links: Link Cited by: §1.

- Collective design anticipation. Futures 120. External Links: Link Cited by: §1.

- Knowledge Gaps — Wikimedia Research 2030. External Links: Link Cited by: §2.1.